Warning: this will be somewhat picture-heavy, and may be a bit self-indulgent…

I’m sure I’m not alone in being a bit of a stationery geek: I can’t be the only person out there who feels a sense of longing when faced with shelves of beautiful blank notebooks in Waterstone’s, who lusts after Moleskines, who has bought a Traveler’s Notebook not because she needed to document a journey but rather for the sheer joy of possession. I do, however, tend to suffer from a paralysing indecision when confronted with the notebook of my dreams: what should I use it for? What should I write in it? What if I write the wrong thing, mess it up, make myself sound stupid or self-aggrandising or… Argh! Better just to put the book on the bookcase, untouched, and just admire it in its pure state, right?

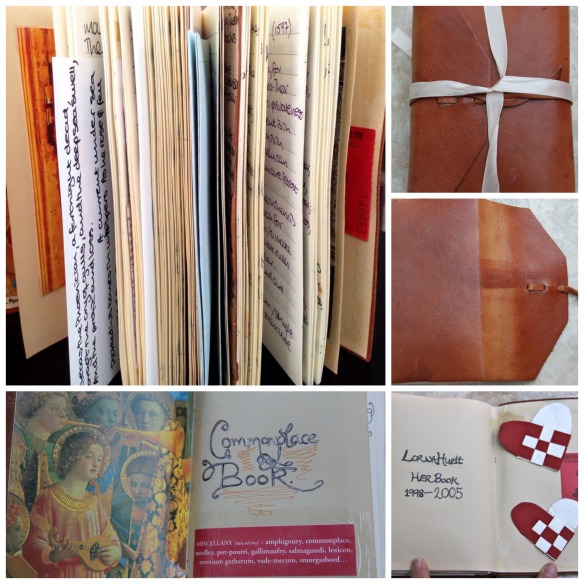

One Christmas back in the mid-nineties, my uncle gave me what was, in those days, pretty much the platonic notebook. He brought it from America, and I had never seen anything quite like it before. It had thick, creamy pages, it was bound in soft leather and fastened with a thong. Basically, it looked like the sort of volume in which Leonardo da Vinci would have sketched embryonic helicopters, in which Count Almásy would record his affairs and his study of African geology alike, in which Dr Jones senior might document his search for the Holy Grail.1 I loved that notebook with all the strength of my unreasoning passion for stationery, but, of course, I hadn’t got a clue what to do with it. I kept it, untouched, until I went to university. There, studying Renaissance and eighteenth-century literature, I encountered the concept of the commonplace book, and all at once I knew what I was going to write.

A commonplace book is, in essence, a sort of literary scrapbook: it’s a repository for extracts from and observations on whatever books the maker might be reading or studying at the time. Sometimes these observations are arranged thematically (John Locke, for example, came up with an influential method of compiling an index to such a book), but mine was more or less a chronological compilation of extracts, added because they resonated with something I was working on at the time. I added to it gradually, sometimes writing a great deal, and sometimes abandoning it for months at a time until another text piqued my interest. I finished my degree, moved to Leeds to study for an MA, then to Preston to teach part-time, then to Florence to take short courses in Italian and Art History. The commonplace book came with me, gradually becoming fatter, more battered, more stuffed with quotations. I finally finished it during the early stages of my PhD, and, for some time, the Commonplace lived on my bookcase, unopened. Recently, though, I took it down from the shelf and began to re-read the entries I had made. It feels horribly vain to say this, but I found it a very beguiling experience: some passages were very familiar, while others seemed to have been written by another person: a lot of time has passed, and I am no longer working in academia. If pressed for a quotation now, I’d probably be just as likely to come up with a line from one of Eoin’s story books. Re-reading the commonplace book was like looking into the life of the person I once was and, far from being the reductive, navel-gazing experience you might imagine, it was actually really interesting.

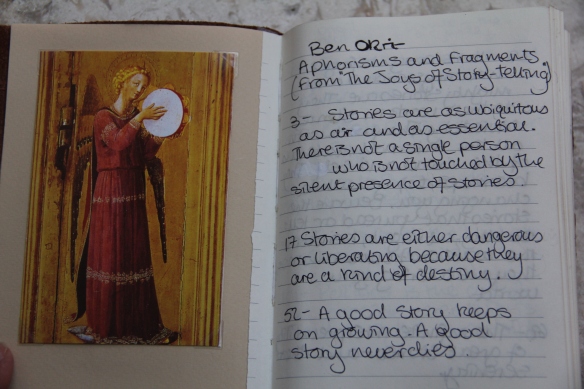

Although I did not consciously make an effort to order my book thematically, a number of distinct patterns emerge. A lot of the entries are concerned with stories and storytelling: the first entry is a selection from an essay on narrative by Ben Okri, which I found in one of those tiny 60p paperbacks which were all over the place in the mid-nineties. Remember the Penguin 60s? I was an indiscriminate collector both of these and the Phoenix versions, from which I took this extract.

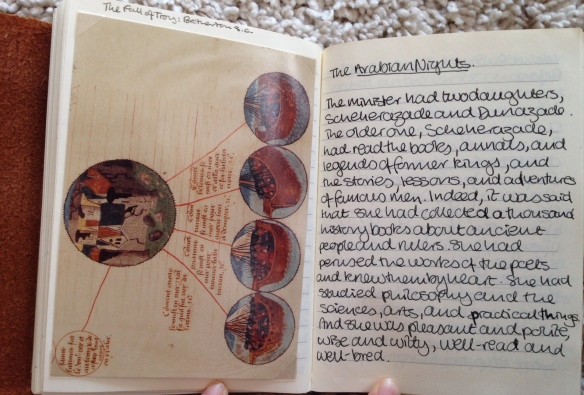

Of course, no reflection on stories and storytelling would be complete without a passage from the Arabian Nights:

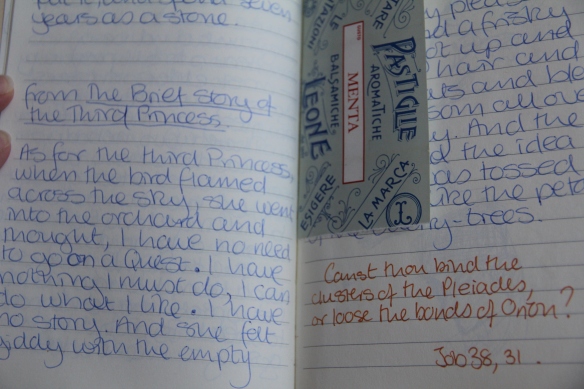

The manuscript illumination on the facing page concerns the popular medieval myth of the Fall of Troy and the founding of Britain. Elsewhere, I’ve inserted some passages from A.S. Byatt’s collection of fairy stories, The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye. The quotation below is from “The Story of the Eldest Princess”: here, in defiance of the usual fairy tale tradition, the eldest princess of three refuses to fall prey to the usual hubris of elder children in quest-fables, and instead forges her own destiny. The quest is then fulfilled by her sister, the second princess, while the youngest princess realises that she is left with no story: “She felt giddy with the empty space around her, a not entirely pleasant feeling. And a frisky little wind got up and ruffled her hair and her petticoats and blew bits of blossom all over the blue sky. And the princess had the idea that she was tossed and blown like the petals of the cherry trees”.

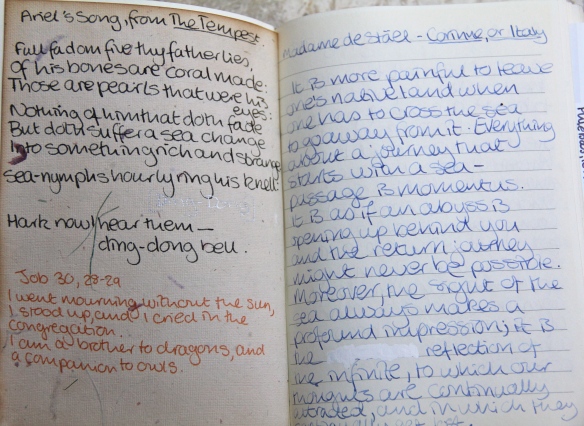

As you can see from this opening, I’ve also quoted from the Book of Job. Reading through the book, there’s a certain amount of Biblical and liturgical quotation, which is unsurprising given that a lot of the literature I was studying at the time was steeped in these traditions. But, my word, there’s a lot of Job. I happen to remember the reason I wrote down this passage: it’s engraved on a glass panel in Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge (because I’m a good librarian, I found the record here).

There’s more Job elsewhere in the book, alongside Shakespeare and Madame de Stäel: in this case, I think the passage stuck in my mind because reminded me of Lord Sepulchrave in Titus Groan (it’s the owls).

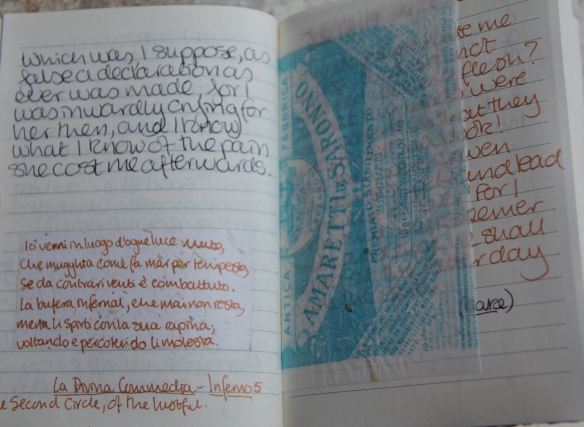

Hidden under this amaretto wrapper is yet more Job (it was, in passing, the first amaretto I ate: I was amazed by the fact that you could light the papers and watch them float): owls excepted, I think the fascination with the particular book stemmed from the fact that I was reading a lot of Blake and listening to a lot of Vaughan Williams at the time of writing. Hey, I was a Cambridge undergraduate: being a bit pretentious was practically in the job description.

This passage and the Dante on the previous page were both added after I’d visited the Tate and spent a long time admiring the Blakes (obviously: see above) and Rossettis.

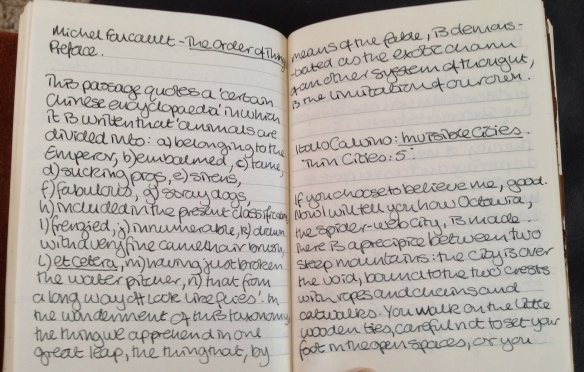

Other frequently-occurring topics, appropriate for an embryonic librarian, were heteroclite collections and unusual taxonomies. As a postgraduate, I did a lot of work on Victorian periodicals: my MA dissertation was on representations of the Great Exhibition in the popular press, which meant that my fascination with apparently unrelated artefacts and texts being jammed together into one varied, eccentric entity was particularly strong at that point. I still love this passage from Foucault which I found at that time, on the arbitrary nature of the ordering principles behind some collections (I wish the Chinese encyclopedia were real, though sadly I suspect that it isn’t):

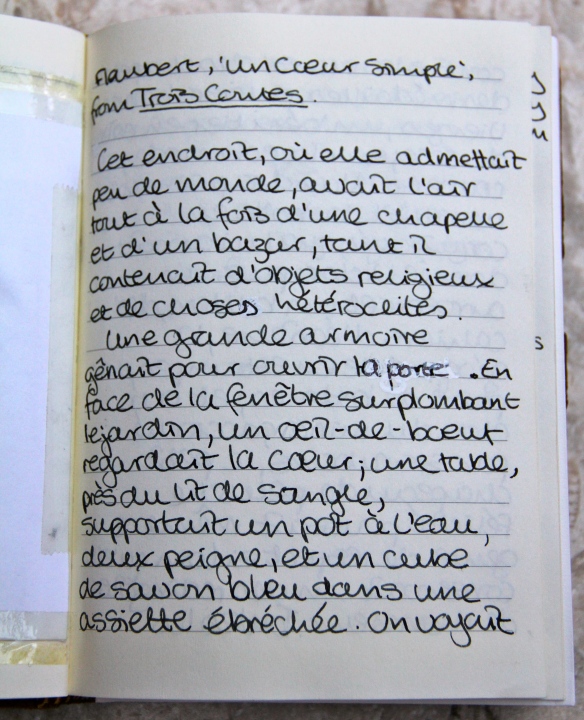

This is the beginning of the description of Felicité’s bedroom in “Un cœur simple” by Flaubert: the passage continues, enumerating the pieces of bric-a-brac and the unconsidered trifles the old woman has collected, and which have meaning only for her, and, of course, for the reader.

I’ve just noticed that past-me made a mistake in passage above: “peigne” should, of course, be “peignes”. Oh, the shame…

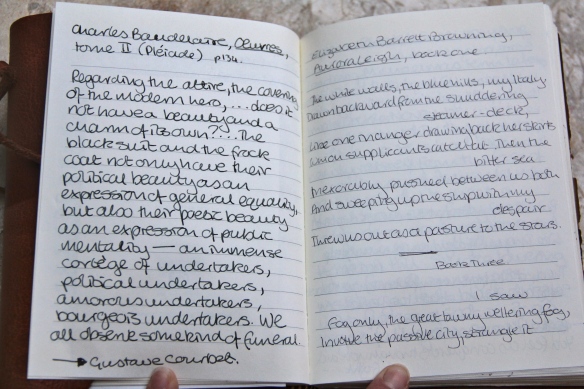

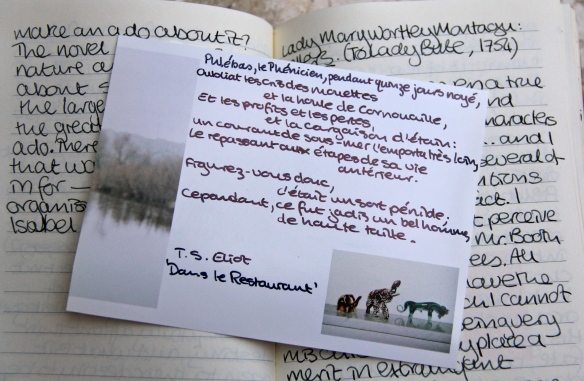

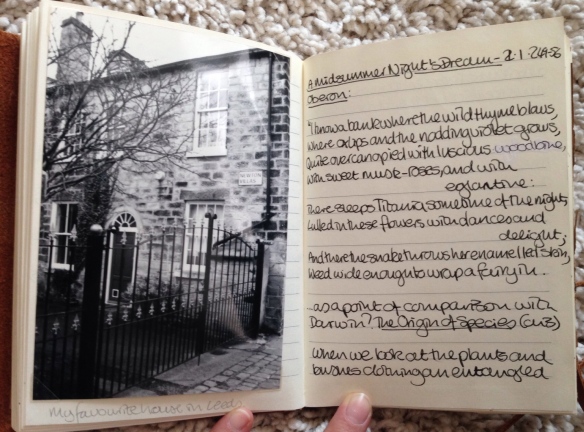

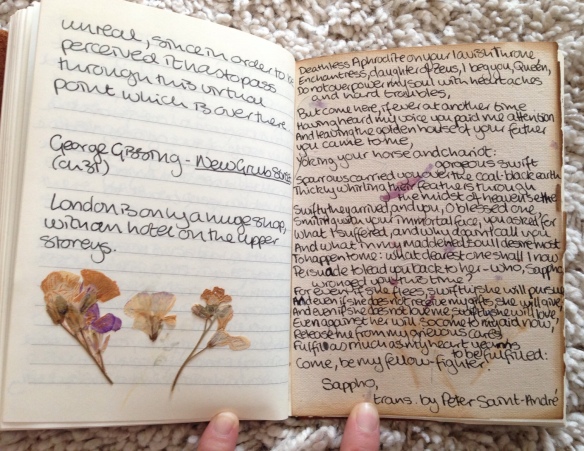

Most of the extracts, though, simply passages which caught my attention, without any real thematic connection. As well as Flaubert, there’s Baudelaire and Barrett-Browning, Eliot, Shakespeare and Sappho.

Lest anyone worry that I was getting really above myself when I added the Sappho, I should note that Buffy fans may recognise it from the last episode of Season 4 (it’s the poem Willow paints on Tara’s back in “Restless”): I got access to a television during my MA, and it somewhat toned down my attempts to be intellectual!

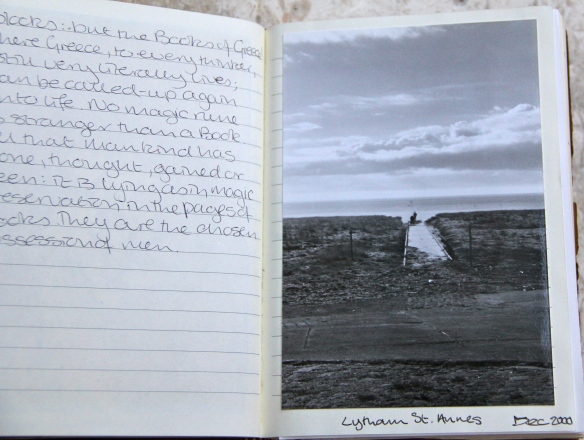

Historically, many commonplace books were beautiful, lavishly illustrated documents: Henry Tiffin’s commonplace book in the Phillips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum, documented here, is one of the loveliest I’ve seen. Similarly, judging from the evidence of Pinterest, an awful lot of people now keep a sort of commonplace book in the form of an illustrated journal, typically heavily decorated with scraps, stickers and washi tape, and often very beautiful. My book was made a long time before these techniques became popular, and I don’t have anything approaching Henry Tiffin’s artistic ability. As you can see, though, I did add photographs, postcards, tickets and suchlike to my commonplace book. Some photographs, like this one of the sea at Lytham, were fairly successful.

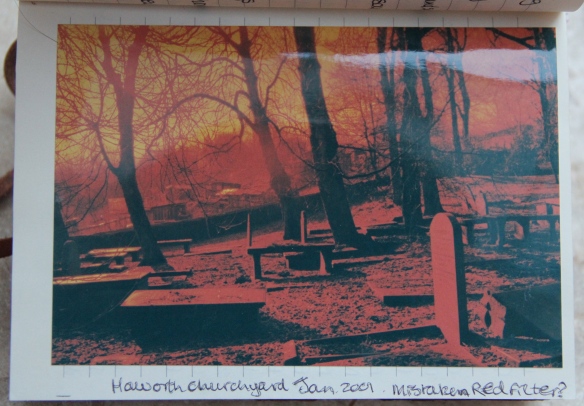

Others, like this view of Haworth churchyard, were more questionable: I had forgotten I was using a colour film instead of a black and white one, and took all my pictures that day with the addition of a red filter.

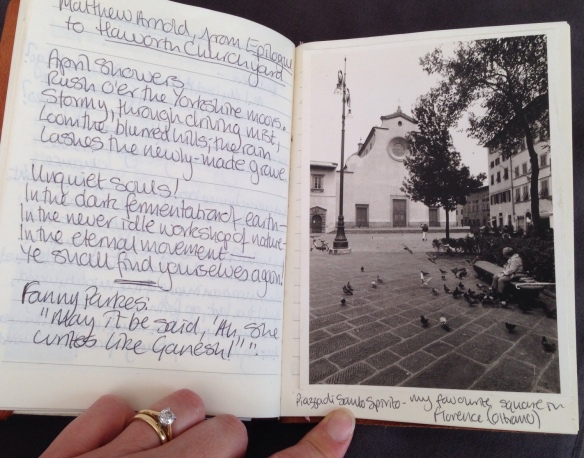

As you can see, it ended up looking rather as if I had taken a day trip to Hades instead of to the Brontë Parsonage Museum. Later on, evidently while I was still thinking about the Brontës and Haworth, I added a postcard of my favourite square in Florence, the less-fashionable Piazza Santo Spirito:

I finally completed the commonplace book during the early years of my PhD: though I tried to start another one at the time, my heart was, for some reason, not in it. I wrapped my finished book up, put it away, and carried on living an un-recorded life. Looking back on it now, though, after some years, I find that the book I made, while it would not win any prizes for being a well-planned aesthetic object, is really rather dear to me. It’s a sort of a time-capsule in volume form, a glimpse back into the life I had a decade and a half ago. Indeed, for the first time in years, I felt the urge to start another commonplace book: I found a Moleskine, wrote my name and the date on the endpaper, and started collecting. I doubt that this book will be in any way as stereotypically learned as the first, made as it was with all the zeal of a student of English Literature. It will, however, be a reflection of my life now (tellingly, it already contains quotations from Elizabeth Zimmerman and Maurice Sendak, and an extract from the Dewey Decimal Classification), and that, after all, is part of the point.

1Apologies for the declining seriousness of these comparisons: I did say it was the mid-nineties, didn’t I?

Ahhh a lot of this resonates with me… the desirability but high intimidation factor of beautiful notebooks, the undergraduate pretension, the Penguin 60s. But the bit that drove me to comment was YES YES SANTO SPIRITO so the best bit of Florence.

I might need to start a commonplace book myself now… this is the second mention of such I’ve come across in the past week.

It really is the best square: the Basilica, La Casalinga, the summer bar in the centre of the square where I once somehow got served a half-pint of tequila for about L10,000… You should definitely start a commonplace book, though: all the best people are doing it! *looks pointedly at @samanthahalf, and at Helen in the next comment*

Hello! Yes, I’ve just started one after a throwaway comment by Lorna got me fascinated by the idea as a way back into creativity: kind of a personal attempt at a sort of less-filled-with-spiritual-nonsense ‘Artists’ Way’.

At the moment I’m using it as a sort of reading log, analysing and copying in quotations from books I’ve read just because I liked the writing or theme or what have you, and there’s a fair few chunks of poetry and interesting images in there. There’s also a fair chunk of other stuff e.g. JK Rowling quotes and internet cartoons.

I decided to be me in my book, even if it felt childish or pretentious – I read something in Steal Like An Artist about authenticity and trying to squash internal critical voices that try to stop you, and decided to just go ahead and put in what I liked.

That said, I am feeling a little like I’m faking it till I make it in terms of creative recovery: but by ‘faking’ my commonplace book, and faking ‘being good at writing’ and faking ‘knitting and sewing’ I am of course actually DOING the things. So it’s working. And pretty: I’m using my fountain pens (thanks again Lorna!) and doodling and putting images in. I might have to investigate this wonderous tape of which you speak, Lorna!

I’m a great believer in faking it. Good plan. And yeah! DOING THE STUFF!

Yes, I certainly second the faking it until you make it idea: it’s pretty much how I do most things! I think Sam is right, too, about being yourself instead of trying to assume a persona. I didn’t do a lot of annotating in my book, but everything I wrote down was something I really loved or was, at the very least, interested in at the time. It’s pleasantly surprising to see how much of it isn’t embarrassing, at least to me: I still love Dickens and The Tempest and Lewis Carroll, and I would probably still copy out similar passages if I were to be making the book today. If anything, the things I’m disconnected from are the passages which are more redolent of academia, as it’s a very long time since I’ve been in that enviroment. In a way, I’m a little terrified of student-me: apparently, I read Walpole and Benjamin and all sorts of stuff!

Hah – I was reading your notes thinking ‘HANG ON she read a Flaubert that wasn’t Madame Bovary! Who knew of such a thing!’

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Tales_(Flaubert) Well worth a look: there’s a truculent parrot.

Go Lorna! A fascinating post. I too am inspired to think seriously about starting such a book…

You should! Yours would involve actual academic thought, unlike mine…

I absolutely love this post. Not because I recognise many if any of the pieces of literature you’ve so carefully collected – but because I totally understand the whole notebook thing, have always had a wee stack of beautiful notebooks that may or may not ever get used, and adore and completely recognise the life before your current life concept. It is fascinating, surreal and humorous looking back and I’m sure looking back through those pages truly takes you to almost another world with another you in it. X

Thank you! As I said in another comment, it’s pleasantly surprising how much of it is not mortifying, though it really does feel as if a different person (a more-interesting, better-read person!) wrote a lot of the pieces down. I’m really glad, too, that I’m not the only person out there with a notebook obsession!

…and in a bizarre turn, I have just decided I wanted to include my comment above in my book as a ‘note to self’, so I’ve printed it for sticking in later ;D

See: paratextual stuff FTW!

Pingback: The power of the post-it: on studying, sensemaking and stationery | The mongoose librarian